Rows: 7,788

Columns: 14

$ id <dbl> 4873463, 16736650, 14999877, 5955860, 15655208, 4…

$ name <chr> "Cozy Pied-a-Terre, the Heart of DC", "Large, wel…

$ property_type <chr> "Apartment", "Apartment", "Apartment", "Apartment…

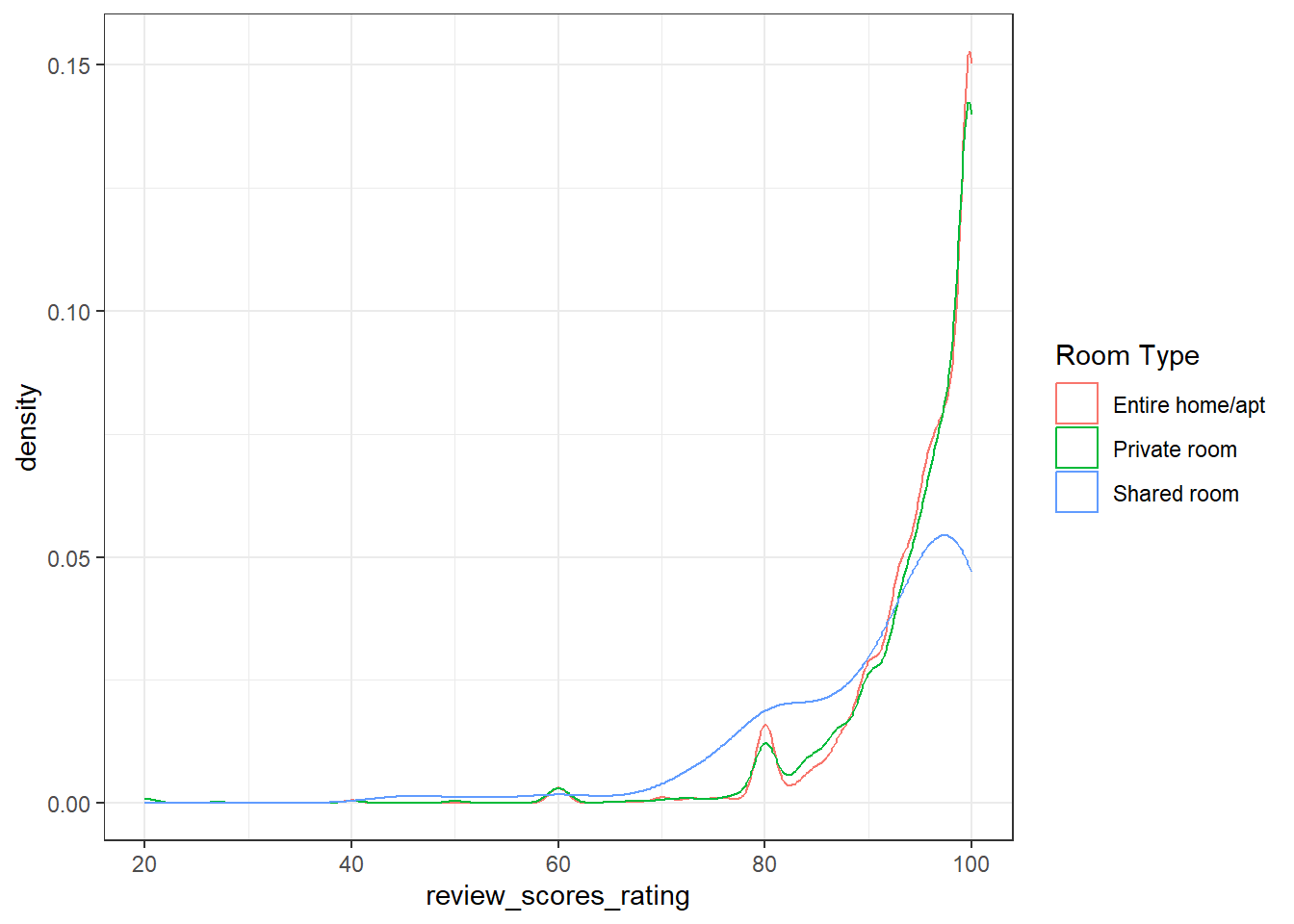

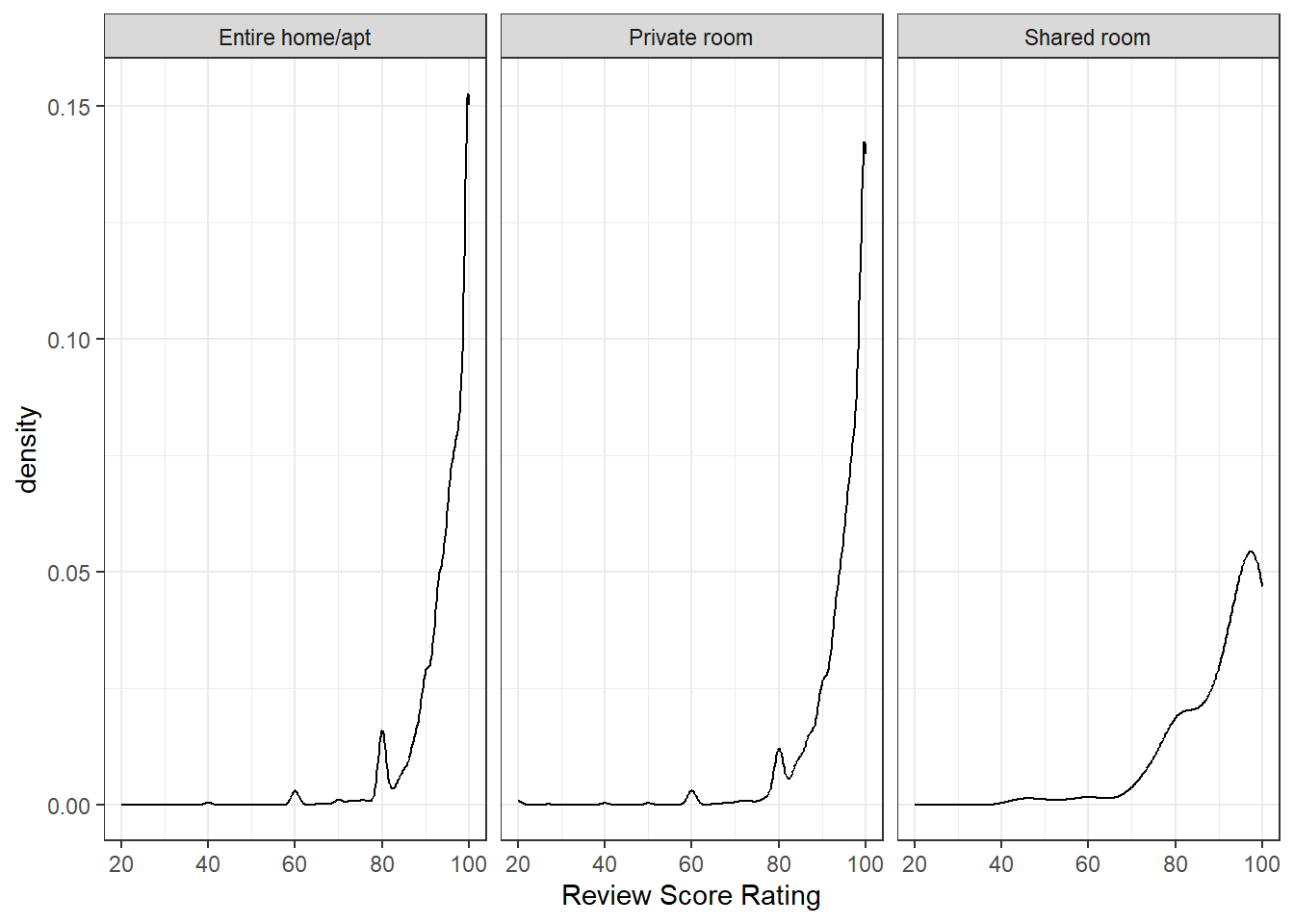

$ room_type <chr> "Entire home/apt", "Entire home/apt", "Entire hom…

$ accommodates <dbl> 3, 2, 2, 3, 4, 2, 3, 2, 4, 2, 4, 3, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2…

$ bathrooms <dbl> 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 2.5, 2.5, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0,…

$ bedrooms <dbl> 0, 0, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0, 1…

$ price <dbl> 95, 200, 100, 129, 500, 110, 225, 79, 172, 110, 1…

$ extra_people <dbl> 10, 0, 0, 50, 0, 15, 20, 0, 0, 10, 0, 0, 0, 0, 20…

$ minimum_nights <dbl> 2, 1, 27, 2, 2, 6, 3, 3, 1, 1, 2, 1, 2, 3, 7, 2, …

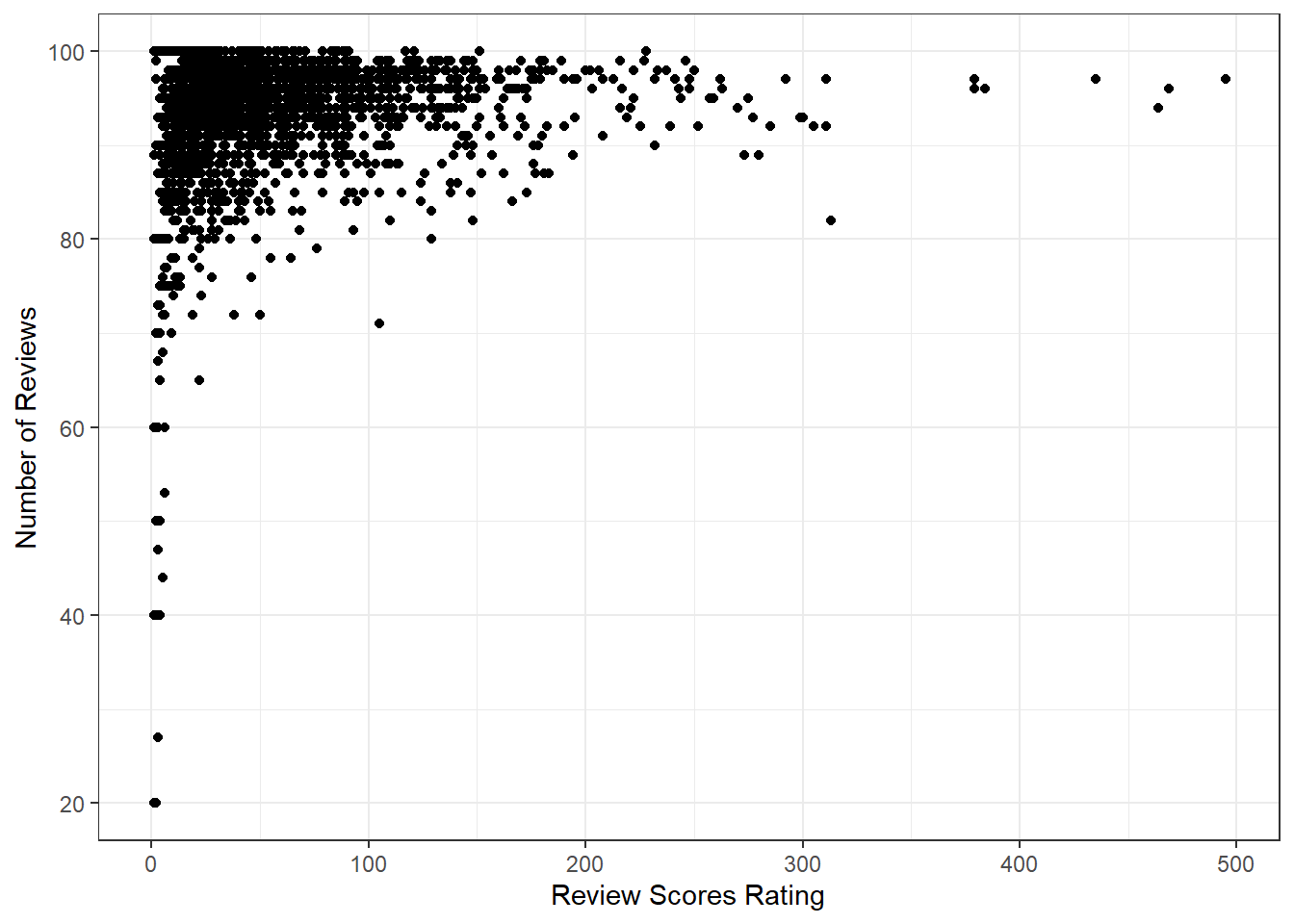

$ number_of_reviews <dbl> 29, 2, 0, 79, 1, 7, 3, 4, 24, 4, 0, 0, 23, 3, 6, …

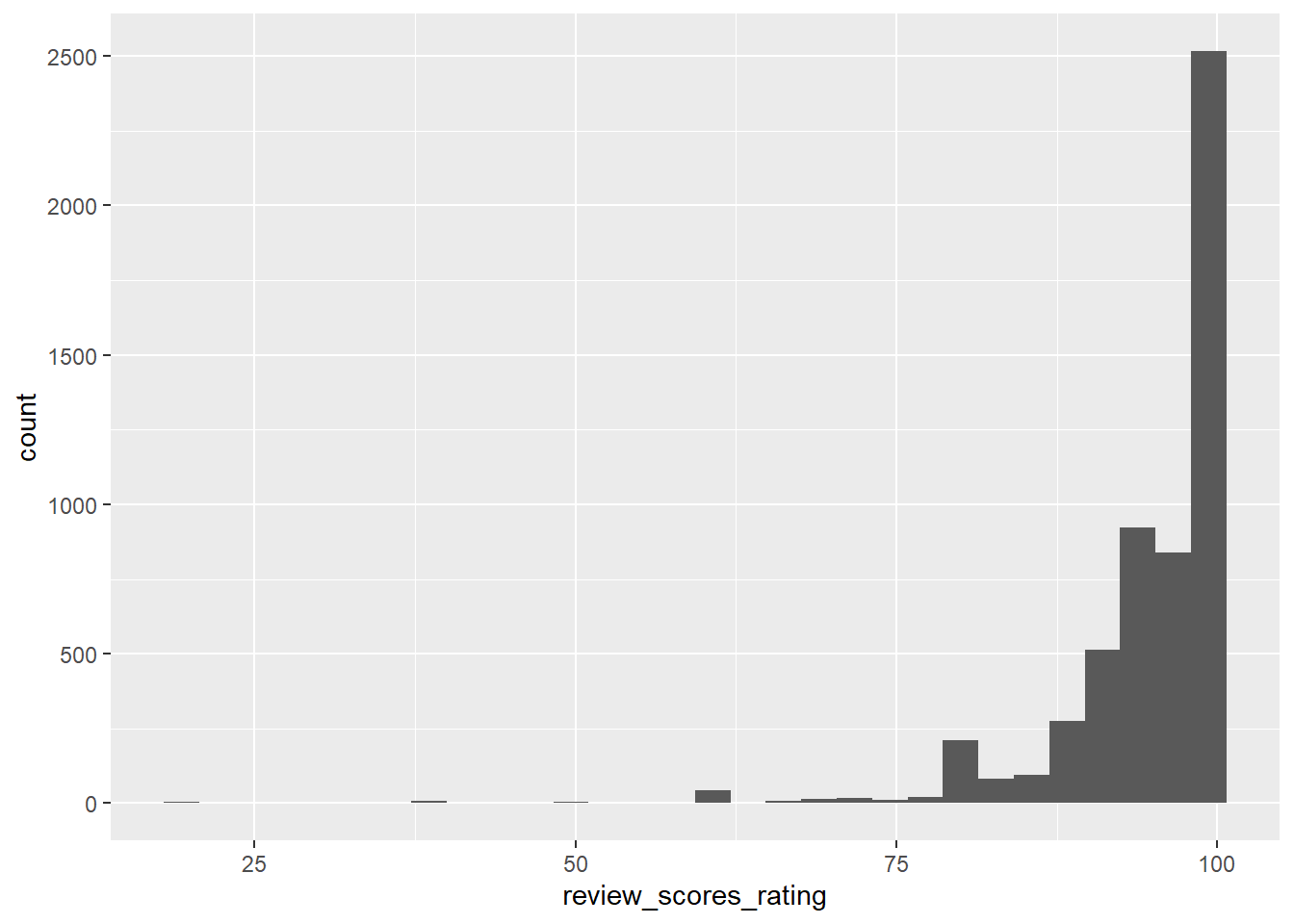

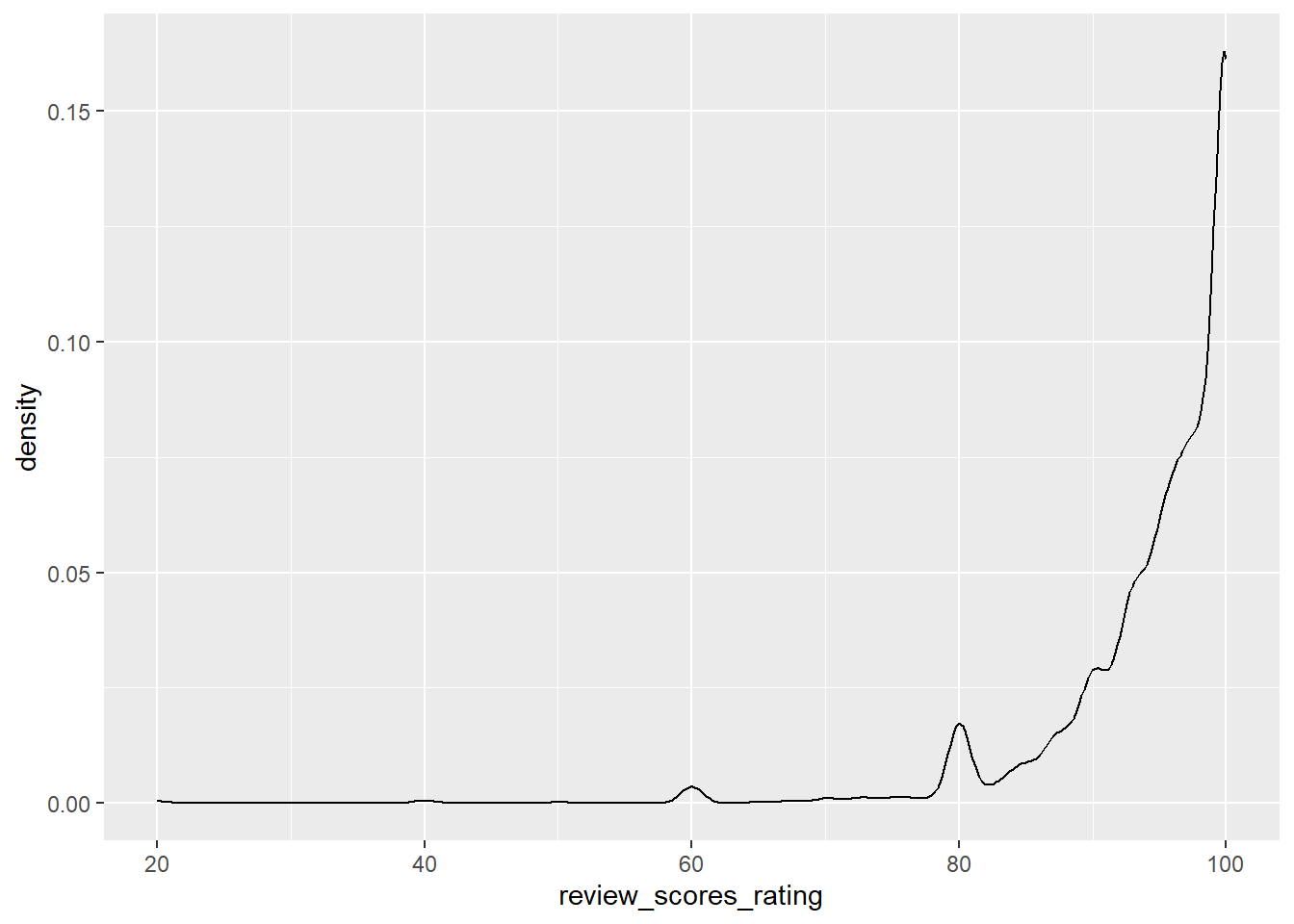

$ review_scores_rating <dbl> 94, 90, NA, 85, 100, 97, 100, 89, 88, 100, NA, NA…

$ cancellation_policy <chr> "flexible", "flexible", "moderate", "flexible", "…

$ reviews_per_month <dbl> 1.01, 0.55, NA, 3.13, 1.00, 0.23, 0.82, 0.09, 0.4…